The 19th century mathematician Ada Lovelace is considered “the prophet of the computer age” not only because she wrote the first computer program, but because she also recognized the far-ranging applications of the nascent computing technology. Even before her major accomplishments, Ada showed great mathematical skill at a young age. Through her work with Charles Babbage, the first person to describe a computer-- or, as he called it, the Analytical Engine--, Ada led to the invention and development of the computer.

Born in 1815 to the legendary poet Lord Byron, Ada Byron showed herself to be a mathematical prodigy at an early age. She always pursued her mathematical interests, despite the discouragement her family showed because she was a girl. She was fascinated by equations and numbers, and found solving a math problem extremely rewarding. She once described that solving a problem “made a lovely shape in her head”. However, in 1827, Ada’s mother interrupted her plans, insisting that she pursue ‘useful’ and ‘moral’ interests, because fascination with science was considered improper for a girl. Undeterred, Ada continued her studies and met William Turner, who introduced her to Charles Babbage's ideas and inventions.

|

| Charles Babbage |

At a banquet, Ada heard an intriguing snatch of conversation. William was discussing Babbage’s newly invented Difference Engine, a machine that performed basic mathematical operations. Babbage’s Difference Engine was an application of the rules of finite differences, capable of adding and storing numbers. She watched intently as he turned a dial on the tangle of cogs and wires, numbers beginning to appear on the machine’s brass wheels. With each turn of the dial, the numbers increased by two. When the machine reached 178, the crowd was beginning to fall asleep...until the machine displayed an entirely different number. He had programmed the machine to add 201 to the number obtained after 89 rotations. Ada visited Babbage many times after this, and learned of his new plan for an improved Difference Engine-- the Analytical Engine. This was to be the first computer. Even though it was never constructed, detailed plans existed on paper. These plans led to the construction of the computer. Although the Difference Engine seems like nothing but an elaborate calculator to people today, it laid the foundation for future computer technology.

|

| The Difference Engine |

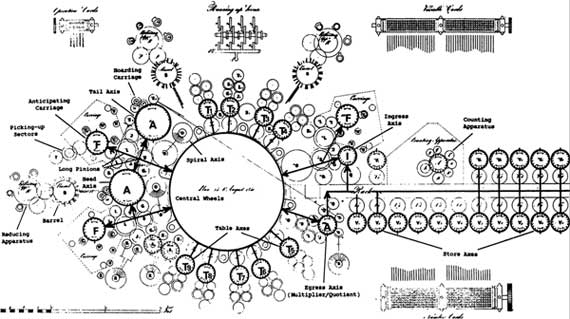

The Analytical Engine was to have more applications than the Difference Engine, and have a far more complicated structure. How exactly was the Analytical Engine different? Unlike the Difference Engine, which required numbers to be entered by a human, the Analytical Engine used punched cards to do this job. It was also capable of performing more complicated mathematical operations, and needed to be much larger to accommodate all its components. One set of cards determined the operations for the adding and multiplying states of the Analytical Engine. Another set of cards distributed the operations according to a particular function, providing the engine with data and obtainable results. The machine was comprised of four components: the mill, the store, the reader, and the printer. These components are the essential elements of every computer today. The mill was the calculating unit, the equivalent to the central processing unit (CPU) in a modern computer. The store was where data was held, analogous to memory and storage in today’s computers. The reader and printer were the input and output devices. Although today’s computers are more complex, the planned Analytical Engine laid the foundation for the development of computer technology.

|

| Part of the plans for the Analytical Engine |

Not only did Ada contribute to the invention of the Analytical Engine, but she also paved the way for computer programming with the code she wrote for the Analytical Engine. At a presentation of his ideas, Babbage met the Italian mathematician Luigi Menabrea, who was interested in writing a book about the Analytical Engine. However, there was only one problem when the book was published: it was written in French. Due to her voluminous education, Ada was fluent in French. Thus, Babbage referred to Ada to translate the book into English. As well as translating the book, Ada added intricately detailed notes further describing the machine, and its possible applications.

In fact, Ada realized something about the Analytical Engine that even Babbage did not see. She saw that, just because one was using numbers in their device, they did not need to be thinking just about numbers. Every computer is doing arithmetic underneath due to its binary code, whether someone is listening to music or programming it to add. Ada was the first to observe possible uses for the computer outside of mathematics, such as composing music. Ada also understood the potential power this machine had, because it could make choices and repeat instructions. In translating and adding to Menabrea’s writing, Ada emphasized the machine’s versatility, explaining how it could solve trigonometric functions including variables, and how it could solve challenging math problems.

Ada’s work with Babbage led to the development of the Analytical Engine, which laid the foundation for the computers we use today. In her honor, the first computer programming language was named ‘Ada’.

Thanks! I never read that much about Ada! Very interesting article. Where did you get your sources?

ReplyDeleteGirl Knows Tech from girlknowstech.com (i can't really pick a profile from your comment system, it's sad) :(

Thank you! I used these books: The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage, by Sydney Padua, and Ada Lovelace: The Computer Wizard of Victorian England, by Lucy Lethbridge. I also used these articles: http://mentalfloss.com/article/53131/ada-lovelace-first-computer-programmer

ReplyDeletehttp://www.computerhistory.org/babbage/engines/